Case of the Bhaniarawala Phenomenon

The recent violence between Akali groups and the Dera Sacha Sauda in Punjab underscores the existence of a number of ‘deras’ in various parts of the state, which are but a manifestation of prevailing caste divisions and tensions. Dalits and other marginalised groups adhere to such deras for it promises them an alternative to mainstream, and in many respects, exclusionary Sikhism. Yet deras, especially in recent decades, have acquired strategic political overtones. This article by Meeta and Rajiv Lochan in Economic & Political Weekly looks at one such episode in Punjab’s recent religious history.

The recent clash between the followers of the Dera Sacha Sauda and various Sikh organisations brought Punjab to a grinding halt for five days. Matters continue to simmer and tempers have been little alleviated even after the dera chief, bearing the multireligious name of “Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh”, was forced to offer an apology of sorts for hurting Sikh sentiments. Various Sikh organisations led by the Akal Takht, the chief temporal seat of the Sikhs, have asked the state government to take appropriate punitive action against the dera chief for having shown gross irreverence to the Sikh gurus, as the Akalis claimed. A call for the social boycott of all the followers of the dera too was issued. The dera chief was called to present himself before the Akal Takht and apologise for his sacrilegious behaviour. The dera chief, for his part, initially refused to apologise, or to present himself before the Sikhs, as he claimed that he had done no wrong. His followers went on to use the visual media to argue publicly with representatives of the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee (SGPC), even quoting from the Sikh scriptures on live TV, in support of their sect leader. After much violence across the state of Punjab, punctuated by some extremist Sikh organisations laying a price on the head of the dera chief, the latter issued a clarification of sorts wherein he said that a misunderstanding appeared to be at the root of the hurt evinced by the Sikhs for neither had he dishonoured any Sikh guru nor had he the intentions to do so. Throughout this public face-off between the Dera Sacha Sauda and the Sikhs one thing became clear: that the dera, its leaders and followers, would not hesitate in publicly proclaiming and practising their version of a religion. The sect’s followers have been doing so for several years now, occasionally even obtaining the support of the state government, especially when the Congress was in power. The Dera Sacha Sauda had been instrumental in the vidhan sabha elections earlier this year, as most newspapers have reported, in helping garner 20 seats for the Congress from the Malwa region. This area had hitherto been an Akali stronghold. How far the dera was responsible for Congress “victories” remains, however, a matter of speculation; what is clear, though, is that the Akalis held the dera answerable for the defeat of some of its candidates.

Once the Akalis came to form a government of their own in Punjab in 2007, they lost little time in taking umbrage at the public posturing of the dera and asserted, in the name of all Sikhs, that the dera chief had hurt their religious sentiments and should apologise for the hurt that he had caused the Sikh psyche. Beginning from May 14, thousands of Sikhs were mobilised all over Punjab and neighbouring states demanding appropriate punishment for the dera and its chief. All the while the state authorities provided tacit support to the agitated and armed mobs by not making any serious effort at crowd control. Later, after the dera chief had tendered his explanation, the chief of the state police claimed, in a press interview on May 19, that the police was perfectly capable of taking strong steps against those carrying weapons in public, violating prohibitory orders and destroying property. However, he added that inaction was the bestaction possible for crowd control in that surcharged atmosphere. On the fourth day of the face-off, a dera follower even approached the Punjab and Haryana High Court with a Public Interest Litigation requesting that the court intervene and direct the state government to provide protection to the life and properties of the followers of the Dera Sacha Sauda. Many commentators noted with concern that an analogous conflict between another dera and the Sikhs in the late 1970s, with the tacit support of political parties to both sides in the conflict, had sown the seeds of terrorism in Punjab during the 1980s. Such conflicts between sects and dominant Sikhism seem to be rather very commonplace in the recent history of Punjab and their significance goes far beyond the short-term politics of revenge. Some receive more public attention than others, some are more complicated, but the basic story behind the conflict remains the same. This article concerns one such conflict that did not draw as much public attention but which, for that very reason, is so much the easier to understand.

One of the more lasting ironies of most successful religions is that they address themselves to universal values and goodness. Yet, there is a strong element of exclusionism within them that separates one religion from the other. This is especially in the practice of the adherents of the religion who, ironically, may be actually going against its tenets in the name of upholding the core ideas of the religion. But what happens when those excluded too claim to be adherents of the religion? Something of this problem has been facing Sikhism in the recent past. At least from among the dalits and other marginalised people of Punjab, a strand of thought has begun to emerge that rebels against the exclusionist and reactionary tendencies within mainstream Sikhism in Punjab, tendencies that have continued to linger contrary to the mission and ideas of the gurus. One such strand engendered a major drama recently. This concerned the emergence of a new sect led by one who was born a dalit Sikh but who even went on to, it is alleged, craft a new ‘granth’ for his followers. This was the socalled sect of Bhaniarawala. His actions touched a raw nerve in Sikh polity and society but did not seem to spark off much thought or debate. In this paper we document this “episode” in Punjab’s recent religious history and suggest that it is imperative for the Sikhs, rather than Sikhism, to address the social turmoil reflected by, what we call, the Bhaniarawala phenomenon. Until a constructive solution is found, a commitment to the idea of ‘sarbat da bhala’ (well-being of all humanity), as the main teaching of the Sikhs believes, remains problematic in public domain and would be confined to the practices of individuals alone. We concern ourselves in this paper with this episode that generated much noise and resulted in the suppression, at least for the moment, of what was seen as an alternate guru movement in Punjab. This one was mostly made up of dalits, most of them were of the mazhabi caste and claimed adherence to Sikhism. What made this one different was its vigorous conflict with the Sikh establishment in Punjab. The mazhabis are the most numerous among scheduled caste groups in Punjab according to the census of 2001. Their population in 2001 was recorded at just a little over 22 lakhs. They constituted some 31 per cent of the total SC population of the state. They are the ones with the lowest literacy rate (42.3 per cent) among the SCs in Punjab, more than one-third among them have an educational level below the primary level and only 15 per cent have more than a middle school education. More than half (55.2 per cent) of the mazhabis work as agricultural labourers. Most of them (60 per cent) were recorded by the census of 2001 as belonging to the Sikh religion and the remaining as Hindus. Only a negligible numbernumber (0.5 per cent) was reported as Buddhists. Obviously, Sikhism plays an important role in their lives. Yet, they seemed to have problems with it, especially with the domination of Sikhism by the upper castes.

A number of other guru panths already exist in Punjab. Some of the more well known ones include the Radha Soamis, the Namdharis, the Nirankaris, the Handalis, the Minas and the Udasis. Of these which ones which are classified as “Sikh sects” remains a matter of debate and personal feeling. Some of these evoke far stronger feelings of rejection as Sikhs. These include the Dera Sacha Sauda and the Divya Jyoti Sansthan. In the early 1980s there was much controversy caused by the burning of the texts called Avtar Bani and Yug Purush that were attributed to the Nirankari baba. Some historians have even attributed the clash between the Nirankaris and the Sikhs, as important in the creation of terrorism in Punjab. Apart from these well known sects there are also hundreds of deras that dot the present day Punjab and Haryana countryside. Perhaps, as Dipankar Gupta puts it, since the 1980s all this has been a part of creating a “Sikh” identity.2 In this story of the deras and babas the one of Bhaniara was actually too small and moreover too narrow in its geographical spread. Yet it had an impressive following and was quick in throwing up a challenge to the dominant Sikh groups. The number of followers of Baba Bhaniara was put at anything from 20,000 to 6,00,000. It was alleged that the guru had penned a granth of his own for the benefit of his followers and had adopted the accoutrements of the gurus of Sikhism. Moreover, this was the only guru movement that excited statewide protests and was suppressed by the government machinery. It concerned a number of issues: the protest by at least one group of dalits against the domination of the present day SGPC and upper castes over the gurdwaras and by implication the Akal Takht, the ability of the dominant groups to mobilise state support for their control over the gurdwaras and expressions of religion and the strong response from the people of Punjab to the perceived threat to religion, especially from those adopting the iconic emblems of the Sikh gurus. For secular threats by dalits mounted within the mainstream Sikh tradition such as happened in the Talhan case, it is interesting to note that the mainstream Sikhs felt far more helpless in responding. Evidently the accoutrements of religion lend much needed legitimacy to the parties in a secular conflict.

By now it is well recognised that there is a thick line dividing Sikh studies. Perhaps there is a similar one dividing Sikhs as well. On one side are the western trained and located scholars and on the other are those trained and located in India. Or perhaps the line that divides is not of the east and the west but of those who reside in Punjab and remain proximate to it and those outside of it. There is a little bit of grey area between the two caused by a certain overlap, but on the whole the geographical divide remains. The discussions in at least one of the seminars, mainly attended by the western trained and situated scholars which had identified one such divide also noticed that much of the difference emanates from the location of the SGPC and Akal Takht at Amritsar and the negative influence that the politicking within them has on any thinking on Sikh history and understanding the practice of Sikhism and the various streams that go into its making.4 We might also recall that for some time now the SGPC and the Akal Takht routinely issue edicts prohibiting any discussion of the Adi Granth and other texts of the Sikh religion that does not resonate with the dominant interpretation of Sikhism. Religious texts need to be believed in and not interpreted, is the broad instruction issued on such occasions. Similar was the contention of one of the leading Sikh scholars from India. Speaking at the Centre for South Asia Studies at the University of California, on the meaning of inter-religious dialogue, he laid down what he thought were the ground rules for understanding a religious tradition. “The point is that a religious tradition must be approached in terms of its own self-definition, in terms of its self-defined identity”, he said. And went on to add that “This requires an unmediated, experiential insight (through socio-religious osmosis) which is not possible in the case of the ‘outsiders’, whatever be their cerebral brilliance”. The fact that this scholar was also the vice chancellor of one of the major universities devoted to the Punjabi language and Sikh studies is enough for us to take such remarks seriously. An implication of such a situation is that a number of issues that need discussion simply get swept under the carpet in the name of being unimportant or too controversial. The dalits of Punjab, the largest body of dalits in the country and collectively, the most prosperous ones, are simply sidelined. Their concerns too are brushed aside. In the recent past, though, the dalits have refused to take things lying down. One such episode concerned the adoption of guru-like diacritical marks by a local religious leader, one Piara Singh Bhaniara.

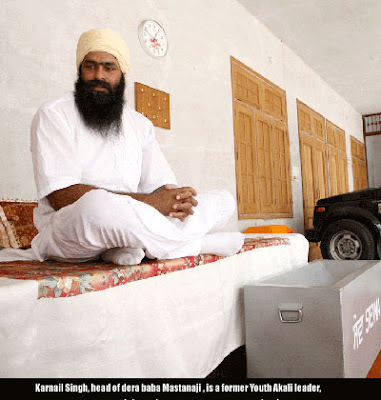

Piara Singh, one of the seven children of a mason Tulsi Ram from the village Dhamiana in Ropar district had been working as a class IV employee with the state horticulture department at a sericulture farm in Asmanpur village. His father had been the caretaker of two mazaars on the outskirts of the village Dhamiana. At the death of his father, Piara Singh became the caretaker of the mazaars. Soon he also came to be known as a healer, providing medicines for various ailments. His reputation grew since people believed that he did have healing powers. He soon came to be addressed as a ‘baba’, a local holy man. In course of time even the then union home minister, Buta Singh, who subsequently went on to become the governor of Bihar, solicited his advice in treating his wife’s illness. As Baba Bhaniara’s reputation grew, so did his number of followers. It was said by the newspapers at one time that he had 20,000 followers across the state. Most of them were mazhabis. But the large number of politicians who flocked to him for help during the elections and offered the Baba help in constructing his dera over 100 acres at Dhamiana suggests that the police estimate of 6,00,000 followers was also held as true, at least by some of the significant political parties in Punjab. In 1998, the jathedar of the Akal Takht even excommunicated Baba Bhaniara for being anti-Sikh for Bhaniara was prone to say “nasty” things about the Sikh religion and its contemporary leaders. This would have ironic consequences later in 2001 when Baba Bhaniara would refuse to obey summons from the Akal Takht when that august body wanted to chastise Bhaniara for having too large a following. On that occasion Baba Bhaniara excused himself from the paying court to the Akal Takht saying that he was still excommunicated and therefore not liable to obey to commands of the Sikh leaders.

During the summer of 2000, it is said, one of the followers of the Baba Bhaniara was denied permission to carry the Guru Granth Sahib from the local gurdwara for some religious ceremony at home. The practice of carrying home the holy book from a nearby gurdwara with due ceremony is a common one. Equally common are refusals to allow the holy book into the hands of those who are disapproved of by the upper caste custodians and management of the gurdwaras. This in turn sparked off a movement among the followers of the Baba to have a granth of their own over which the dominant sections of society did not have any control. In the next few months the baba along with some of his close followers began to create this new granth. The resultant granth was given the name of Bhavsagar Samundar Amrit Vani. It is said that it was mostly written by one Pritam Singh of Dudhike village in Moga district with the help of some 20 other followers including six women. The frontispiece of the completed granth had a picture of Baba Bhaniara sitting beside his wife Surjit Kaur and writing the granth. The date given for the commencement of writing was June 20, 2000. After his arrest, though, the baba denied having penned the granth and that he had merely dictated it to his followers. On Baisakhi day in 2001, Baba Bhaniara “released” the granth, all of 2,704 pages, at a function in his dera. It was an impressive text, written on large sheets of paper with an expensive binding. Physically, it was big in size and heavy to hold. It contained a number of photographs of various politicians visiting the Baba. The typewritten text was photocopied and distributed among followers. A printer in Chandigarh was assigned the task of printing it.

The followers of the baba even began to hold religious ceremonies with the Bhavsagar granth at the centre. At one such ceremony in Ludhiana, in September 2001, the recently formed Khalsa Action Force, one of the numerous fly-by-night organisations that emerge in Punjab for a brief while, attacked the function, snatched the granth and set it on fire. It was said that the granth had copied a number of portions from the Guru Granth Sahib. In one of the photographs it showed Baba Bhaniara, wearing a shining coat and headdress in a style similar to that made familiar through the popular posters of Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth guru of the Sikhs. In another Baba Bhaniara is shown riding a horse in the manner of Guru Gobind Singh. Not only this, Baba Bhaniara insisted that his sons be addressed as ‘sahibzadas’ in the manner of title used to address the sonsof the gurus. The Bhavsagar granth itself narrated a number of stories about the greatness of the baba, the good luck that he brought to those who believed in him and the punishments that befell those who criticised or taunted him.

The attack on an assembly of Baba Bhaniara’s followers and the burning of the Bhavsagar granth was immediately followed by a number of instances of the burning of the Guru Granth Sahib in various rural gurdwaras. The police was quick to arrest a few young men from different villages and even presented them before the media. In front of the media they accepted that they had burnt the Guru Granth Sahib at the instance of Baba Bhaniara. That in turn sparked off a cycle of violence against the baba and his followers who were accused of dishonouring the Sikh holy book. Soon enough the baba was arrested under the National Security Act and a number of criminal cases slapped against him. Many of his followers were put in jail. In the prison they were attacked with acid and knives by other inmates claiming adherence to Sikhism. The Bhavsagar granth was banned by the government. The copies under circulation were confiscated. Any one found in possession of a copy was arrested. The print ready copy was taken away by the police and perhaps destroyed. Baba Bhaniara’s various deras across the state were destroyed. At least in a few places the deras were forcibly converted into Sikh gurdwaras and brought under the administration of the SGPC. No action was taken against those who had perpetrated these attacks.

Politicians who had been “close” to Baba Bhaniara were castigated by the Akal Takht and made to undergo punishment for their misdeeds. Many of them refuted any closeness to the baba, pleaded their innocence, underwent the punishment and gave public statements asking for even greater punishment by the government to Baba Bhaniara and his followers. The Akali government in power then, with Prakash Singh Badal as chief minister, was accused of being soft on such renegade babas who threatened Sikhism. Various factions of the Akali Dal, and there are almost innumerable of them, began to vie for the mantle of being the true protectors of Sikhism while accusing all others of having encouraged Baba Bhaniara and his renegade religion.

The SGPC set up a three member factfinding committee on the phenomenon of Bhaniarawale. Their report, a 48 page document, listed the various acts of sacrilege that had been committed by the followers of the baba. All this information in the SGPC report had been culled from the newspapers. It indicted several politicians, including the union minister Buta Singh, his nephew Joginder Singh Mann, former Akali MP Amrik Singh Aliwal, former Punjab minister, Gurdev Singh Badal and his son Kewal Badal and others of being responsible directly or indirectly for encouraging, patronising and popularising Bhaniarawala. Besides, it also blamed a number of Nihang leaders and police officers for helping Bhaniarawala in propagating his cult.

After two years in jail, the hearings in the various cases against Baba Bhaniara were still not over. His presence in court was always marked by heavy police arrangement since there were many who still professed the desire of eliminating him for his sacrilegious behaviour towards Sikhism. After his release in 2003 the district magistrate of Ropar under whose jurisdiction Baba Bhaniara’s dera at Dhamiana lay, banned his entry into the district of Ropar. The baba and his followers approached the state high court pleading for the restitution of their fundamental rights. Subsequently that ban was rescinded by the court. Then the baba was asked by the local administration to desist from celebrating his birthday which falls on August 23. He promised to make it a low key affair, but went on to have a large gathering of his followers at the dera. By now the ban on his birthday celebrations have almost become a ritual. The government bans it, yet people assemble in great numbers. The next day newspapers report that the birthday celebrations passed off peacefully. Not much notice is taken by the dominant Sikhs of the activities of Baba Bhaniara. There was one exception, though. This happened when a local gurdwara in Ropar allowed the followers of Baba Bhaniara to take the Guru Granth Sahib for a private ceremony in 2004. That sparked off yet another round of protests from the SGPC and many Sikh organisations.

However, by now a different party, the Congress had formed a government in the state. The controversy over the baba and the relationship that he and his followers have with Sikhism remains unresolved but at least he has desisted from taking public postures, for the time being at least.

It is easy to see the above episode as another instance of political wheelingdealing in the name of religion. But such an interpretation denies us two important issues. One, that the symbiosis that has evolved in Punjab between political power and religious authority has become the creator of a variegated drama in which political machinations dominate in the name of religion. Two, that the dalits of Punjab (and also many other marginal groups) have begun to assert themselves in ways that demonstrate the limits of control by the dominant groups and challenge their domineering claims to represent true Sikhism. Thus far and no further, seems to be the message that they are sending. This could easily, as in the Baba Bhaniara case, lead to the assertion of a different religious identity altogether. But the closeness that any new religious identity has with the emblems and iconic practices of Sikhism creates a drama of its own whereby routinely edicts are passed as to who has the right to interpret religion and preach it and who has not. The list of those who cannot goes on lengthening day by day.

In a rather ironic sort of way then, what this means in effect is that contemporary Sikhism, insofar as it has been defined by the politically dominant factions, is able to reiterate its distinctive identity mostly through exclusionism. In the past two decades or so this has amounted to creating a new phenomenon: that of declaring people renegade from the panth and demanding that a return to the fold will be possible only through the acceptance of some punishment. Declaring people ‘tankhaiya’ (renegades from religion) and asking them to present themselves before the Akal Takht has become routine and driven by political exigencies. All the space for debate, discussion, consultation with the people, qualities that had marked the growth of Sikhism, seems to have vanished. So much so that recently, as seen in the case of the launching of the journal The Spokesman by its owner Joginder Singh, a well known dissident, it was possible for those declared tankhaiya to publicly ignore the orders from the Sikh priests and assert that they were not scared of such ungodly orders from a suspect clergy.

The phenomenon of the deras has two implications: one for the larger Sikh tradition and the other for the social fabric in the state of Punjab. Firstly in any religious tradition, no individual or body of individuals can or should lay claim to a superior truth for there is really nothing to say why any one’s claim is better than that of another. To do so damages the body of belief from which individual opinions emerge by the simple act of seeking to restrict its boundaries. If a religious tradition is to be approached only in terms of its own self-definition, as some insiders assert, then the definition needs to be as broad as possible if it wishes to avoid being determined by an oligopoly. Perhaps the Sikhs need to remind themselves that the whole is more than the sum of its parts. Secondly, as a social phenomenon, the various religious sects of Punjab are part of the time-tested tradition of the dispossessed in India seeking a sense of personal worth through dissent. One of the greatest religions of the world, Buddhism, began in precisely such a fashion. To suppress social dissent through the use of the state machinery or other forms of violence does not mean that the dissent would disappear. Rather as long as it is allowed to find religious expression, dissent remains harmless. Its suppression through secular means could well transform it into a force of a different kind and the recent history of Punjab does not offer much scope for optimism in this respect.